Beekeeping in Vancouver

City Farmer founding director, Kerry Banks, wrote an article on beekeeping for our first issue of City Farmer Newspaper in August, 1978, titled "Outlaw Bees Keep City Blooming".

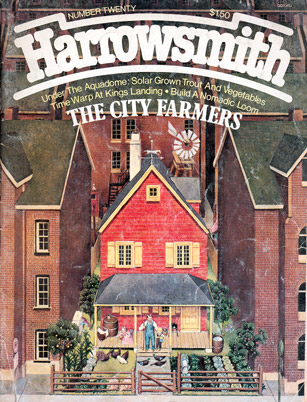

In the summer of 1979, Harrowsmith Magazine, impressed by our concept of urban agriculture, produced a whole issue titled "The City Farmers" and asked Kerry to expand his original City Farmer article for them. Below is his 1978/79 report on Vancouver beekeepers.

Kerry Banks is an award-winning magazine journalist and sports columnist. He has published 17 books on sports, including a biography of superstar hockey player, Pavel Bure. [August 2021]

Outlaw Bees

Keep your hedges high, your head low and your neighbour's honey jar well-filled

By Kerry Banks

Harrowsmith Magazine

July 1979

"It shall be unlawful for any person to keep horses, cattle, swine, sheep or goats or to keep any live poultry or fowl including ducks, geese, turkeys, chickens or members of the pigeon family other than registered homing pigeons or to operate any apiary or otherwise keep bees for any purpose in the city."

The last few words of Vancouver city bylaw number 4387, section 72, make Bill Chalmers something of a small-time criminal. A gentle graduate student in his early 30s, Chalmers leads, in all-important respects, a law-abiding life. But a man, it seems, is known and made guilty by the company he keeps. Bill Chalmers, one of probably hundreds of illegally practising apiarists in Vancouver, shares his backyard with 70,000 bees.

At first glance it appears to be a backyard like many others. There is a lawn, a hedge, a rosebush, some lilacs and a sizeable vegetable garden. But the tiered wooden boxes discreetly situated beside the hedge give Chalmers away. Zigzagging insects hover around the garden, and the air is alive with a low and incessant hum. Near the base of the closest hive is a seething mass of black and amber insects.

"They're young ones," Chalmers tells me, "just out catching a little bit of sun."

Throughout most of Canada, the matter of cosmopolitan "livestock," including bees, is usually legislated by individual cities. An exception is Ontario, which has a provincial "Bees Act" stating: "No person in an urban municipality or suburban district . . . shall place or leave hives containing bees within 100 feet of a property line ...." Professor Philip Burke of the University of Guelph admits, "That pretty well excludes having them on a city lot. "

Elsewhere, the limits of apiculture are generally defined under "health" (in Vancouver) or "nuisance" (in Calgary) legislation, and everywhere the bylaws are generally overlooked by beekeepers and officials alike, unless neighbours are especially alarmed by swarms or stings. "Fortunately," says Chalmers, "the city won't take any action against a beekeeper unless there's a specific complaint." Outlaw bees buzz in every city from Victoria to Halifax, and apiarists like Chalmers have connections with each other-through clubs and courses -that link them into one of the most blatant networks of lawbrakers.

Bill Chalmers maintains contacts with beekeepers through his work with the botany department of the University of British Columbia. In five years of raising bees in his backyard, he has received few complaints from his neighbours and some actually appreciates the insects' pollinating activities. "One fellow two doors down even fills up his birdbath every morning with water for them," he says. He did, however, "stretch the neighbours' patience a little thin," he admits, when his backyard hives grew to 15 in number. He now has a more manageable two, with another dozen out of town in Aldergrove, where beekeeping is legal.

It is difficult to say how many people in Vancouver raise bees. Understandably, they are not exactly standing up to be counted. There are, however, 1,500 apiarists in the B.C. lower mainland, so clearly there are a fair number in the city. But city apiarists are for the most part a quiet lot who go about their business in modest seclusion, their hives tucked discreetly behind a high fence or hedge.

Hidden Benefits

Actually, most urbanites may owe something to the hidden beekeepers. Although bumblebee queens appear in early spring- March on the West Coast, April inland -they are far outnumbered by the worker honeybees, who are out in full force by this time, prepared to pollinate flowers and fruit trees before the bumblebee workers finally appear in early summer.

Chalmers himself profits from this side industry. He has a diverse and thriving vegetable garden with squash, melons, cucumbers, carrots, lettuce, rhubarb, tomatoes, beans, turnips and corn. He grows lemon balm as well, because he believes that it has a slightly tranquilizing effect on the bees. (The herb's Latin name, Melissa officinalis, derives from the Greek word for "bee." Lemon balm has long been grown around hives to help prevent swarming.)

Adding to the greenery in the bees' environment is a row of raspberry canes that provides Bill with 20 pounds of berries annually. A winding grapevine covers the roof of the garage, and without special care or cultivation, it yielded 500 pounds of grapes last year. Some of them became grape juice-about 40 quarts of it.

The bees, of course, make it a good place to grow things. "I don't know of a single area in the city where you can't find bees," says Bill, and he points to the lushness of vegetable gardens and fruit trees throughout the city as evidence. Since bees will normally forage only a mile or so from home, it is reasonable to assume that there are more than a few backyards in Vancouver that are not all that they appear to be. The activity of these domestic bees is supplemented by hives of wild honeybees (the result of unharvested swarms that have nested in buildings and trees) and by bumblebees.

The rapid rise in the popularity of city beekeeping followed the sudden hike in the price of sugar a few years ago, the steadily climbing price of honey, and the interest in natural foods and raising them oneself. Actually, it is a resurgence in popularity. Obviously, four or five decades ago enough people wanted to raise livestock in cities that legislation was passed to discourage them. The nuisance and health problems that sometimes accompanied farm animals had proved incompatible with small city lots. Soon, nothing was considered more desirable in the suburban backyard than a well-groomed lawn, Hibachi and a few petunias. But now, the petunias are increasingly taking a second place to tomatoes, and the Hibachi has been moved to make room for beehives.

Chalmers, however, became interested in apiculture while it was still unfashionable. "When I first got involved about 15 years back, it was only the old timers who were raising bees," he says.

"In fact, in my own case, it was an 82-year-old neighbour who first got me started. I'd watched him work with his bees and from time to time he showed me things. Then one day he moved away and left behind his hives. It just so happened that at the same time our neighbours on the other side of us moved too. The family that moved into their house had a pretty young daughter. I was desperate for a way to get her attention, so I claimed the abandoned hives and then invited her to help me with them."

The relationship with the bees turned out to be more lasting than that with the girl-he's been involved with bees ever since.

The way Chalmers learned apiculture, by observing an old hand, was ideal, but it is a path that is open to only a very few. Urbanites are more likely to enroll in a course offered in the evening, or to buy books and magazines on the subject. Nevertheless, the city beekeeper's task is slightly different from that of his fellow in the country.

Halcyon Hives

One of the prime requirements of the urban hive, Chalmers came to learn, is that its inhabitants be gentle. Improperly attended, bees can become feisty and unpredictable. "Sure, occasionally you'll run across mean bees the same as you'll run across mean people. And bees can be nasty when they want to-a mad hive will sting fence posts." Chalmers himself unwittingly accepted a "bad hive" once. It turned out that the bees were so ill-tempered that the original owner hadn't had the nerve to inspect his hive in three years.

One should not buy such stock in the first place. And, according to Chalmers, there are a few recommended ways to avoid propagating such an unruly colony. One is to take care not to damage or kill bees when handling hive frames. Another is to avoid working the bees at the end of a honey flow when they are particularly protective. Still another is to leave the bees alone on overcast days. They are aggressive when the barometer is falling but, like people, are in a much better mood when the sun is shining.

"Bees are basically docile creatures who like nothing better than to be left alone to do their work. In the summer I sunbathe out here on the grass right beside the hives and the bees have never given me any problems. " He says that recent movies like The Swarm and Killer Bees "portray bees in a way that is totally contrary to their true nature. "

To prove his point, Chalmers donned his beekeeper's suit and proceeded to extract one of the hive's comb-laden frames for me. There were hundreds of bees crawling over it.

"Here," he said, offering me his hat and veil. "If you move very slowly and deliberately, you can take hold of this with your bare hands."

I did as instructed, grasping the frame edges in my exposed hands and holding its surprisingly solid weight out in front of me. I could feel the bees humming in my fingers, but not a single one tried to sting.

"Most people panic when a bee comes near," says Chalmers. "The worst thing you can do is get excited and start swatting. If a bee is bothering you, the best course of action is to lower your head and back off." The bees will then be less likely to sting the eyelids.

Understandably, even the most civilized hive of hard-working bees can be a source of anxiety for neighbours, some of whom may be allergic to their stings. Some people harbour an almost hysterical fear of the stinging insects. As a precaution against upsetting one's neighbours, it is a good idea for the city beekeeper to erect a fence or row of shrubbery along the perimeter of his yard. Such a barrier will force the bees to fly upward on their nectar-foraging routes. Once started off at this altitude, the bees will keep to the same flight pattern and thus be far less likely to disturb neighbouring residents.

Also, as bees require as much as two cups of water daily for the maintenance of each hive, it is advisable for the city beekeeper to have a source of calm water nearby. Carolyn Fowler, an apiculturist of two years' standing in the Chicago suburb of Glen Ellyn, has a birdbath beside her pair of hives. She floats small pieces of cork in the water so that the bees have a spot to light and drink. Otherwise, she says, they are likely to journey to other people's birdbaths and swimming pools, possibly causing havoc. Not all neighbours are as accommodating as Bill Chalmers'.

The biggest single concern for the city beekeeper is to prevent one's hive from swarming. The sight of a huge cloud of bees suddenly pouring from a hive and rising into the air is a disconcerting sight for even the most un-derstanding of next door neighbours.

Swarming may occur when a colony becomes too large for its hive and the bees, by some instinctive arrangement, divide themselves into two parties. One accompanies the old queen out to seek its fortune elsewhere, while the other group remains in the hive to begin again with a newly developing queen.

Chalmers says that the most effective method of preventing swarming is to monitor the brood chambers of a hive carefully. It takes 16 days for a new queen to develop, so if the apiarist can go through his hive every two weeks to check for a new queen cell, he should have the situation under control. The queen cell is easy to spot as it is noticeably larger than the other bee cells and it looks like a peanut. If this cell is removed, the urge to swarm will be frustrated, although perhaps not cured.

Evidence of the "underground" apiaries, swarms are not unusual in urban areas, despite the best attempts to keep them from occurring. Occasionally a local radio station will announce the location of a swarm, and such a concentration of bees, complete with queen, represents money to the apiarist. Chalmers recalls hearing just such an announcement on his car radio. Although he drove to the site immediately, he was met by a score of eager beekeepers with boxes and bags at the ready for the valuable booty.

The SPCA and fire and police departments all have lists of local beekeepers they can contact in case of a swarming emergency, and are responsible, in most cases, for the radio announcements. "So really," Bill observes, "even though we are technically outlawed, city officials know who we are and use us to help them."

Backyard beekeeping is not without its commercial benefits especially in the city, where markets are plentiful. Chalmers' two urban hives delivered a total of 400 pounds of honey this past summer, and with honey selling for $1.00 per pound, that meant a tidy return from a backyard hobby.

Besides selling honey, apiarists can turn a profit marketing other related hive products, including beeswax for about $3.00/lb., pollen and propolis (hive resin) for about $5.00/lb., and royal jelly (the queen bee's food) for as much as $25.00 an ounce. In addition, individual queens sell for $5.00.

The novice beekeeper must be prepared to expect a lower yield of honey in the first year, perhaps 50 pounds less per hive, as the newly arrived bees are handicapped by a shortened harvesting season.

On the Canadian West Coast, it is necessary to import the initial stock of bees from California, and a quarter of a million packages of these bees are imported each year into western Canada. They are usually shipped to middlemen who, in turn, sell the bees locally.

The first of two significant honey flows in the Vancouver area peaks in late April. Novices, because of their delayed start, miss out and are forced to wait until the second major honey flow in July to begin to accumulate their honey crop.

All going well, by the second year, beekeepers can expect to double their first year's honey harvest.

It is no longer as inexpensive as it once was to get started in beekeeping. Unless the beginner decides to build his own-a difficult venture-it will cost approximately $80.00 for a fair sized hive. A three-pound stock of bees will cost another $30.00.

Protective coveralls, gloves and a veil will add another $30.00. The beginner will likely need to buy a smoker, at about $15.00, to help pacify the bees during hive inspections. There will be other incidental expenses for pollen substitutes and antibiotics to be used in early spring feedings. Come the end of the season, if he has decided to produce liquid honey rather than comb, he will need an extractor. New extractors run as high as $550.00, so it is advisable to either borrow or buy one second-hand. An experienced apiarist will often allow the novice to use his extractor, for a fee.

Total cost estimate without an extractor comes to $175.00, with an extractor, as much as $725.00. Obviously, one is not going to recoup this investment in the first season, and possibly not in the second, either. Optimally, the new beekeeper will have spent time around hives before buying his own, and will know if he likes working with the tiny creatures. Although I wasn't stung by Chalmers' bees, the apiarist must expect the occasional sting.

The Bee Year

In Vancouver, the beekeeping year begins in late February, with the first warming trends of spring. Since November, the hives will have been left to function on their own. Providing the bees have been left a sufficient supply of honey from the previous summer, there should be little problem. Through the winter, the hive population will naturally decline, but not so drastically that, with some early spring management, the beekeeper cannot have a thriving colony by April.

February is the time when bees begin their own spring cleaning. As the weather continues to warm up, workers will haul out the weak bees that died inside during the cold weather. A pile of dead bees around the hive in late winter or early spring is desirable; it means that the hive has survived and that the bees inside are back at work.

Starting in late February, beekeepers supplement the hive's food supply with syrup mixtures laced with antibiotics. This special feeding is used in place of nectar and pollen to build up the is colony's strength and to prevent disease.

A great deal of research has gone into attempts to find the most effective pollen substitute, including yeasts, com oil, potato flour, powdered milk and even meat scraps. Of these, Chalmers recommends brewer's yeast. It is more nutritious than any of the others he says and oddly enough, it is less expensive, at only 30 to 50 cents a pound, as compared with $1.00 and up for the others.

However, after several more years of his own research, Chalmers hopes he will have discovered an even more suitable pollen substitute. Last season he fed all of his bees a herring meal mixture. Apparently herring meal is even higher in protein than the other available pollen substitutes and can be bought in Vancouver for only 25 cents a pound. It is fed to the bees in the form of a solid patty (at the rate of one pound per week per hive); they take well to it, and there is no transfer of fishy taste or odour to the final honey product. One of Chalmers' herring-fed colonies produced 350 pounds of honey last year. He attributes their high productivity to the herring meal, which, in some areas of BC can be bought from feed stores (where it is sold as chicken feed) and herring processors. Chalmers, however, recommends that the beekeeper not rely solely upon this feed until more testing is done. (He has applied for government funding to explore this new pollen substitute.)

As soon as natural pollen becomes available in the spring, the bees will cease feeding on the pollen substitute and will become wholly intent on gathering nectar from early blooming plants, unintentionally accomplishing pollination at the same time.

Throughout the spring, hives should be inspected on a biweekly schedule to insure that the queen is still alive and laying and that conditions are not ripe for swarming.

As weather warms, bees begin reproducing rapidly and, at peak periods in the summer, the queen may lay 2,000 eggs a day. A worker bee's life expectancy during the honey harvest is a mere six weeks, so there must be a constant turnover in the hive's population.

During the honey flow, extra boxes (supers) may be added and those that are 80 per cent or more filled with honey, removed. Colonies usually gain from one to 15 pounds of honey weight a day in the summer.

Robber Bees

By August, the nectar supply is drying up and the honey flow coming to an end. It is now advisable for keepers to take supers off the hives. The resultant smaller hive area will concentrate the bees, allowing them to stay warmer and defend the hive against invaders.

It is in late summer when the phenomenon of hive robbing is most prevalent. At such times beekeepers invite calamity if they leave their hives open or neglect to put away scattered bits of comb. Foraging bees from other domestic or wild hives will be lured by the smell of honey and begin making off with the colony's supply. The robber bees will then return to their own hives and bring back reinforcements. The resulting chaos can be a harrowing experience.

"It's just as if the bees were crazed honey addicts," says Chalmers. "They appear from everywhere and start crawling in windows and all over the doors of your house trying to find more of it.

At summer's end, Chalmers leaves behind two supers on each hive about half full with honey, as the bees will need 60 to 70 pounds to last them through the winter.

As an added precaution at this time, he partially closes off the hive entrance with a small piece of wood or metal, making it easier for the inhabitants to defend themselves against robbers.

When November and the cold weather roll in, he removes the entrance restriction and opens up a small hole on the lid or one of the sides of the hive to allow for ventilation.

In a climate such as Vancouver's, winter is not so severe as to warrant insulation for a hive, but it is necessary virtually everywhere else in Canada. Here the bees will keep warm by clustering closely together near the top of the hive. They are able to withstand temperature drops to four degrees below zero F with no ill effects. Because of the damp climate, however, Vancouverites must provide adequate ventilation to prevent the risk of having the hive turn mouldy.

The greatest risk to the wintering urban hives is likely to be an invasion of mice, but these can be controlled with an occasional inspection of the hive base.

Until the cycle of bee management begins anew in late February, the hives will appear to the uninitiated to be nothing but a stack of white boxes in a quiet backyard. To the city beekeeper, however, they represent a very real-if illegal-link to nature in a time when such links are not easily come by in the urban environment.

Sources

We urge you not to buy bees or equipment until you have some familiarity with the insects. Take a course or study with an experienced apiarist. Know if you are allergic to bee stings. Bees are usually bought through middlemen who accept orders and buy from sources in the southern U.S.A. Local apiarists will know whom to contact. Also, check the bylaws in your city or municipality. If your hives are confiscated, you will lose your entire investment.

A useful beginner's book is:

The Beekeeper's Handbook By Diana Sammataro and Alphonse Avitabile 131 pages, paperback, $7.95 Available from Harrowsmith Books

Urban Beekeepers No Longer Have To Fly Under The Radar

Link to Courier story shown below

By Cheryl Chan-Contributing writer

published on August 3, 2005

Bryce Ahlstrom has been breaking the law for 10 years. But no longer. On July 21, city council unanimously voted to repeal the bylaw prohibiting beekeeping in Vancouver.

Ahlstrom, a beekeeper at the Strathcona Community Garden in the 700-block of Prior Street, is pleased his previously illicit activity has now been legalized.

The community garden has maintained hives since the 1990s despite a 30-year-old bylaw that prohibited the keeping of bees-as well as horses, donkeys, swine and sheep-within city limits.

Ahlstrom was aware of the obscure bylaw from the beginning. "People who keep bees, they know about it." But in practice, the city has turned a blind eye to beekeeping.

Twenty-six hobby apiarists in Vancouver are registered with the provincial Ministry of Agriculture and Land, while an estimated 10 to 20 more operate under the radar. They do not hide their activities but some keep within the good graces of their neighbours by offering them gifts of honey.

"It's an open secret," said Ahlstrom. "The parks board comes to our open house and looks around, so they know about it. But unless a neighbour complains, you're left alone." In the last decade, the city has received no complaints about honeybees in Vancouver.

There have, however, been complaints from a vocal group of beekeepers who believe the bylaw is an anachronism since beekeeping is occurring in Vancouver backyards anyway, said Shannon Bradley, a social and food policy planner with the city. After a year of research and discussions with the local beekeeping community, council voted to lift the ban and to adopt guidelines for hobby apiarists.

Hobby beekeepers are expected to adhere to good management practices and reasonably prevent swarming and aggressive behavior.

They must also provide an adequate water supply to prevent bees from seeking water in neighbouring swimming pools, ponds or fountains. Hives should be kept in rear yards and limited to two or four, depending on the size of the land.

The guidelines are based on voluntary compliance. Because summer is the height of bee activity, the number of hives at the Strathcona Garden has grown from four to six.

They are propped up on six-foot tall stands near compost piles and underneath shady trees.

The hives require periodic maintenance. "You always check for diseases, and you check to see if they're starting to store honey," said Ahlstrom. "You also want to look and see if there is a functioning queen." If the queen bee dies or gets killed then the number of bees will diminish drastically.

Contrary to public perception, bees are generally harmless. "They will only sting in self-defence. For example, if one gets tangled up in your hair, it might panic and sting you."

But aggressive bees are quite rare, he adds. Responsible beekeepers make sure the queen bee, which produces the workers and dictates the genetic characteristics of the colony, does not have overly aggressive genes. The city considers hobby beekeeping to be part of a broader "urban agriculture" strategy.

Urban beekeeping increases biodiversity and leads to better harvests of fruits and vegetables in city gardens, said Bradley. Ahlstrom agrees. "Honeybees pollinate almost all kinds of flowers and plants." In addition, bees also produce honey, honeycomb, beeswax and royal jelly that can be sold or given away.

But aside from the environmental benefits and business possibilities, Ahlstrom likes bees because they're just plain cool. "You have to be careful and work in a methodical and deliberate manner," he said. "I find it relaxing. There's a lot of technical and biological knowledge that you pick up as you get into it."

He also keeps personal beehives in his backyard in Richmond, where beekeeping has long been legal.

The bylaw amendment is not likely to spur a beekeeping frenzy. "It's such a specialized hobby," said Bradley, "so we're not anticipating a big increase."

Hobby Beekeeping Report to City Council (PDF) July 21, 2005

![[new]](new01.gif)